This interview is part of an ongoing series published by the BIMA Immersive Tech Council which aims to draw attention to the groundbreaking work happening in the area of art, technology, and innovation.

Dr Libby Heaney is an award-winning British artist with a PhD and professional research background in Quantum Information Science. In 2015, Heaney graduated from Central Saint Martins Art School, London. Since 2019, Heaney has been entangling quantum computing with art through her self-written quantum code, games engine technology, video and image-making. In exhibitions, Heaney’s quantum art jostles with physical elements such as slimy glass sculptures, watercolour paintings, and fabric tentacles, creating sensuous worlds that not only speak to the entanglement of the virtual and physical, but also of the past, present and future, body and mind and the human and machine.

The following interview took place in April 2024 between Libby Heaney and Samantha King, Head of Programme at VIVE Arts. The interview has been edited and condensed for length and clarity.

The artist. Courtesy of Libby Heaney.

I’d like to start with the story of your path into creative practice. You have a PhD in Quantum Information Science and have published numerous papers on quantum theory, in particular entanglement. But I understand from an early age you wanted to be an artist. Can you share how your career path evolved to where you are now?

I was always creative, art was by far my favourite subject at school, but I was also very good at maths. I ended up studying physics and German at Imperial College in London. I specialised in quantum physics during my Masters as part of my Erasmus year in Freiburg. Saying that, as soon as I arrived at Imperial I thought, I’ve made a big mistake. I should have studied something creative but I didn’t have the money to and needed a career. So I ended up doing a PhD in quantum physics at the University of Leeds followed by a prestigious postdoctoral fellowship at Oxford University because I found quantum so magical. I also held a post-doctoral position at the National University of Singapore. I found the reality of working in science quite claustrophobic. It was a very male-dominated environment and didn’t suit me. I was still always drawing and painting throughout this time. I think it was then that I began to recognise the artistic potential of quantum. For instance, I would draw with marker pen on both sides of a piece of paper so it became non-binary as the images would merge through and layer over each other. Eventually, I was able to save enough money to go to art school at Central St Martins in 2013 until 2015. I also taught at the Royal College of Art (RCA) as a faculty member from 2014 – 2019. My practice really took off after 2019 when I left the RCA to focus on being an artist full-time.

I think many people may be intimidated by the complex and abstract nature of quantum concepts. You put a lot of work into helping to demystify these concepts through your social channels. Can you share some of those explanations here?

My PhD investigated quantum entanglement in ultra-cold atomic gases. To understand entanglement, you need to understand quantum superposition, which is where one entity is in multiple contradictory states at the same time. You don’t see this in the macroscopic world, but when you observe the microscopic world indirectly you see particles like atoms or photons behaving like this. Imagine you had a football and spun it. If it was a quantum particle, it could spin forwards and backwards at the same time. Quantum superposition is opposite to our intuition and the macroscopic Newtonian reality. Furthermore, the act of observation causes the superposition to collapse. The act of recording irreversibly changes the state of reality. This has been proven in many scientific experiments over the last sixty years. No one really understands why superpositions occur.

Entanglement is superposition extended to more than one entity. The two concepts are intricately linked. So if you have two entangled particles, they can exist together in a joint superposition of all possibilities. But if you try to retrieve an individual particle you destroy the system and the state of the particles goes back to being binary. As an example, you and I are now talking on this call but if we were in an entangled state, we could at the same time as taking this call, both also be walking our dogs somewhere else. Entanglement is a layered stack of possible relations all at once. To fully appreciate it, I think one needs to understand the mathematics behind it because it’s beyond our imagination through language alone.

At the RCA I taught an elective on quantum. It helped me to develop a way of speaking about the science in an accessible way. Scientists would never use words like blurring and layering to talk about quantum.

Libby Heaney’s solo exhibition Ooze Machines at Phoenix Art Space.

How do you reflect those magical qualities of quantum in your artistic practice? And I’d be curious to know if your relationship to quantum concepts has changed as a result of your creative practice?

For me, magic occurs when the seemingly impossible becomes possible, akin to witnessing a magician pulling a rabbit out of a hat. Quantum phenomena evoke a similar sense of wonder. I approach quantum concepts playfully and philosophically in my work.

One of my aims through my art is to push the public’s imagination into the deeply weird aspects of quantum. Through my practice I better understand the connections between phenomena like entanglement and superposition and how they can help us reimagine the binary individualist systems we live within. Art serves as a catalyst for me, symbolising the bursting of the scientific bubble and its seamless integration into every facet of reality. This is where the concept for my new show Ooze Machine in Brighton came from. For the exhibition, I’ve been exploring the relational nature of reality and of the self overflowing. Susanne Wedlich describes this in her book Slime: A Natural History. Everything has a certain ooziness or fluidity at its core.

How do quantum scientists respond to your work? Do you see your work influence their practice?

The arts community really wants art to influence science, but I’m not sure it does in a direct way.

My experience is that scientists consider there to be a hierarchy of knowledge and professions. Scientists, especially physicists, think they sit at the top of that hierarchy because they are touching the “true” reality through mathematics and experiments. I’ve heard comments from the science community that my work doesn’t capture quantum physics correctly. What does this even mean? Scientists think of my art as a tool for the public to communicate with science, or as a conceptual or visual metaphor. But they don’t see it as something that has the same status as science.

However, I do believe art can go beyond science in that it can inspire deep emotions and work with metaphor, fantasy, sensation and embodiment, which deeply resonate with people and this is very important within today’s society.

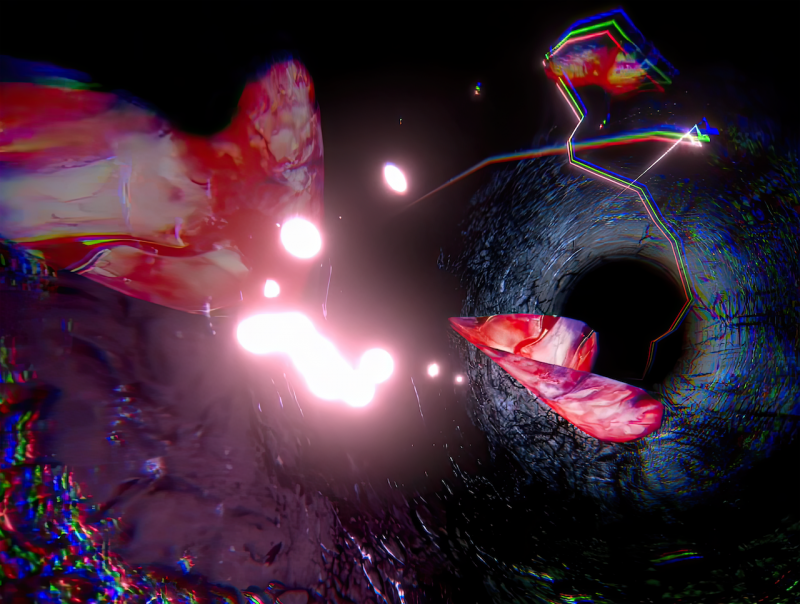

Heartbreak and Magic, 2024. Courtesy of Libby Heaney.

Can you tell us about your recent work Heartbreak and Magic? What was your creative process like to conceive and make this work?

Heartbreak and Magic is a virtual-reality commission by VIVE Arts. It started from R&D and led to a VR work, with its first iteration displayed as a physical installation as a solo show at Somerset House, London. Our early discussions revolved around the concept of quantum entanglement, initially considering the idea of interspecies entanglement.

I started the R&D phase focusing on the body first. Since leaving science I’ve moved away from a rational, scientific way of working to a more fluid and embodied process instead. So for this project, I worked with movement practitioner Naomi Annand to explore entanglement in the body. We started exploring interoception through different pressure points and what resonated for me was my tummy. Under Naomi’s instructions, I would take very slow, minimal movements with a pilates ball pressing into my stomach, just sensing. It was quite an emotional space but at that early stage I didn’t latch onto the emotional narrative of the sensation. I would go home and start writing and making automatic drawings, which eventually formed the ‘storyboard’ for the VR experience. After a few sessions, I realised I was holding a lot of grief in my belly about my sister, Sally, who passed away very suddenly five years ago. So the work pivoted to explore grief, entangling with my inner self, and how I had turned to quantum physics and concepts of superposition, entanglement, and the multiverse for comfort after she died.

Later in the project, I started working with quantum computers creating different kinds of quantum entanglement which were then used to animate or shade different aspects of the VR work. I built my own system in Unity games engine to use the entanglement data from the quantum computer to run lots of different videos concurrently in one scene in the VR (via the GPU). Gabe Stones (the Lead Developer on Heartbreak and Magic) and I then used that system throughout the project.

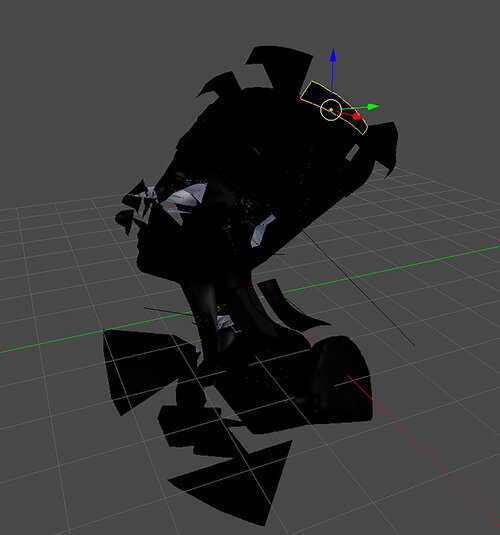

Quantum Fake, 2018. Courtesy of Libby Heaney.

This was the first time that you created a virtual reality work with quantum computing. But let’s talk a bit about your previous virtual-reality works and what the process has been like for you working in that medium?

I made two virtual reality works previously. One in 2017 called Quantum Breathing which drew inspiration from Haruki Murakami book Hard-Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World, commissioned by Science at Home, part of Aarhus University in Denmark. Then in 2018 I made another VR work called Quantum Fake which was commissioned by the Science Gallery in Dublin. I’ve always been fascinated with the medium. VR is amazing for its immersivity. You feel as though you’ve been transported to a different place. I’ve made immersive installations that are projected in a room and while lots of people can be in a projected immersive space at the same time, your brain doesn’t play the same tricks on you as in VR. You don’t have that cognitive embodiment. I think that’s interesting from a quantum perspective. At some point there will be a quantum games engine, where the extra dimensional quality of quantum physics is revealed in real time and that’s when things are going to feel very, very weird.

I’d be interested to hear how you devised the audience journey for Heartbreak and Magic? Can you speak about the physical presentation of the work and the interplay between the VR and other installation elements?

I wanted to create an immersive space that gradually led audience members to the VR, while at the same time opening up various aspects of the process and themes in the work, particularly embodiment. For this, I created several monumental painted scrolls to install in the gallery space. The paintings charted different themes from the non-linear process of making the work – personal histories, the language of quantum physics, the process of working in the game engine, emotions related to my family and my grief. I painted the gallery walls a dark grey-green, a colour taken from Munch’s painting Death Struggle. Very calming, but also intimate. There were also videos – slowed down clips from moments in the VR – in the gallery floor and one on the ceiling. The audience members had to look up and down to see these, which reminds me of how people look around in VR. A soft bench with material that visually echoed the VR environment as well as soft carpet surrounding it, brought attention to people’s bodies. Then the visitor passed through the physical installation beyond some silky curtains into the next layer of reality. They were invited to take off their shoes and stand on another soft carpet. I collaborated with the artist Rosie Gibbons to create skins for the controllers that had little studs on them, echoing elements within the VR. Then they were helped into the headset by the facilitator and would go into the next layer of reality – into the VR artwork.

Installation views of Libby Heaney: Heartbreak and Magic at Somerset House

Heartbreak and Magic, Somerset House, London, February 9th–20th, 2024. Photo credit: Tim Bowditch.

Heartbreak and Magic is a deeply personal work for you. How do you reflect on the very private experience of creating a work with such personal significance to then bringing it into the world? What was it like for you to present Heartbreak & Magic publicly to audiences?

I mentioned my sister passing away in 2019. It was by suicide, which is really hard to understand and work through. During the process of making Heartbreak and Magic, the VR work suddenly took on a life of its own – it became something else, its own thing. It was then I decided I was going to speak about Sally passing from suicide. It’s uncomfortable to talk about for a lot of people, including me. But I feel it’s important to foster open dialogue because the more we talk about suicide, mental health, and grieving, the easier it becomes. Through this collective conversation, we can break down stigma and create space for healing.

Towards the end of the work I realised that Sally is somehow still alive. It was the most difficult work to make but it’s helped me a lot. It seemed to resonate with audiences too. I always want to make work that moves people. I think that can be hard to do with technology based art. So I was pleased that Heartbreak and Magic captured people’s hearts and created empathy and understanding.

This series is focused on how arts and culture are driving innovation. What is your perspective on creative R&D? From an artist’s perspective, what do you think is needed to encourage and support cross-disciplinary collaboration and innovation in this space?

R&D is essential because otherwise you just make the same things again and again. Having the space to experiment allows you to try something entirely new like I did. I didn’t expect to make a project about grief at all, but I’m pleased I did. It was as a result of having space and time to explore which allowed the work to emerge naturally. What artists need is funding, as well as space and time to work. I also think trust is very important because if you don’t have that you need to realise a final artwork very quickly – perhaps even before a commission is agreed. It was important to know the R&D phase would flow into a production phase. I’ve received just R&D funding before and sometimes the work just fizzles out.

Some artists might hate me saying this but being an artist is a business. You have to live. You have to pay for your studio and the people you work with. So if you have sustained engagement and funding you then have more security to make something new.

How do you go about the process of documenting and archiving your work? Are you actively thinking about how to future proof and preserve it given you are using digital tools that are evolving at such a fast pace?

Archiving and documentation is very important. These technologies are evolving at a rapid pace. At the moment, each quantum computer in the world is completely different and you have to write the code to fit that specific quantum computer. Quantum computers are also decommissioned or upgraded. The code that I wrote for a certain IBM quantum computer a few years ago won’t run or output the same results out of a newer quantum computer. Because of this, I document all my work and all my code, even the notes in task management apps I used during the development process like Trello and Slack. I think the process of collaboration, how decisions were made, and how the work evolved is important to document.

Lastly, what’s next for you? Are there any upcoming projects or areas of exploration you are looking forward to?

I’m really excited to announce my first public art commission for Frieze Sculpture London which opens in September. I don’t want to give too much away but there will be both physical and digital elements that open up the public’s consciousness around quantum in new ways. I’ve also been working on a lot of watercolour paintings the last few months exploring how watercolour relates to quantum but also personal narratives and history. I work on wet paper and allow the colours to merge out and interfere and blur and entangle together, and then paint another layer which also blurs and entangles together, and so on. It’s a good metaphor for quantum. I find painting a very personal way of working.

Ent-, Painting, 2021. Courtesy of Libby Heaney.

Related links:

Libby Heaney Studio (website)

Ooze Machines at Phoenix Art Space

Heartbreak and Magic at Somerset House

Quantum Fake at Science Gallery Dublin