Usually, designing physical objects implies first, looking at their intended functions and then figuring out a way to make everything fit into a cohesive design.

In an attempt to answer a breadth of needs such as human interactions and manufacturing processes, a designer has to make decisions that will lead to an elegant solution, the aesthetic value of which being “an inherent part of the function” [1].

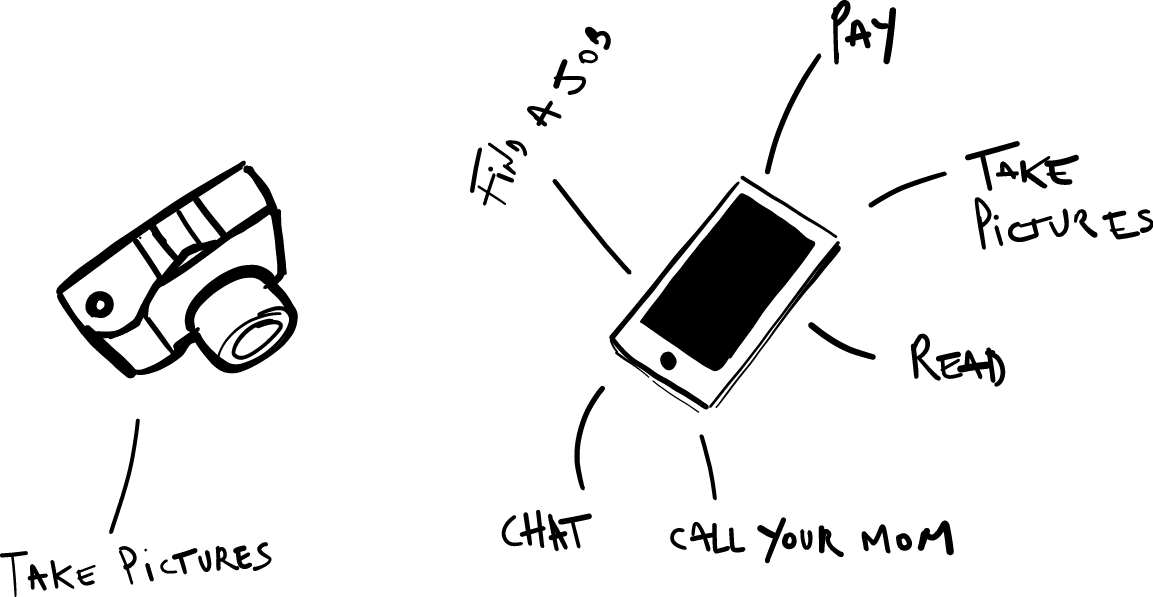

While a standalone camera, for instance, has to offer a grip so it can be held comfortably and provide space for the numerous segments of glass that form a lens, a smartphone, on the other hand, is designed so as the taking-picture function does not disrupt its primary function: being a communication and content consumption tool.

In both cases the shape of the product informs us on what its function is.

This is embodied by the famous design mantra “form follows function” attributed to the American architect Louis Henry Sullivan [2].

Not every designer or architect will agree with this statement of course, but it is fair to say that generally in physical world design (including architecture), form allows function.

On the other end of the spectrum, if we look at the digital world, designers don’t really have to worry about the laws of physics or the limitations of a manufacturing process over another.

In the digital world, it seems that the only remaining artefact of our physical reality is summarised by the question of Skeuomorphism (in interaction design, a physical world mimicry of sorts that stretches from seemingly superficial questions on aesthetics all the way to complex user interaction principles [3])

Undoubtedly, designing a digital product or interface requires coping with user expectations and interaction habits (e.g. scrolling or pinch zooming) but, in effect, spatial limitations are 2-dimensional and non persistent.

Now looking into the future, chances are that many of the objects we use today will be replaced by virtual objects, materialised through Augmented Reality (AR). We might have one physical device, perhaps a pair of glasses, that emulates the objects we usually interact with.

Of course, there will still be physical saucepans and watering cans, but for a large part, objects that keep industrial designers busy today (i.e. watches, smartphones, laptops, cameras and even thermostats) may well be replaced by their virtual counterparts.

This raises an interesting question: What design rule prevails when the physical and the digital worlds collide?

Does everything become a floating User Interface as the most inspiring stock images we see these days seem to suggest?

Or on the contrary, could Skeuomorphism become the go-to design principle of the virtual physicality in an attempt to make AR more acceptable?

And if so, will there be a time reference point?

If Augmented Reality (AR) still might sound like a somewhat distant future, Virtual Reality (VR) is already being used all around the world for numerous gaming and non-gaming applications such as virtual tours, education, medical visualisation and training.

Content has to be created for these simulations and it involves a lot of design happening in the background.

In a way, most of this design work can be considered as prop design: its function is mostly an aesthetic one serving a storytelling goal.

More often than not however, the design work will focus on a virtual product or tool with a complex function, on which the experience might rely entirely.

Not having any physical world limitations as a constraint or a starting point can leave the designer with a feeling of standing in front of a blank canvas. In turn, this is an exciting area for design experimentation.

This is certainly what I realised when we decided to make a VR adaptation of Magic Hour, a photography simulator we had initially developed for iOS [4].

On the iPad version, our design is largely inspired by the existing camera interface to make it as intuitive as possible. In fact, our camera is simply an alteration of the normal view triggered by a button.

For the VR version we soon came to the conclusion that none of these common digital interface abstractions would make sense and that the design of the camera could be crucial to the experience.

As strange as it might sound, our initial idea was to turn the framing into a full-body experience where an ant-sized version of the user gets teleported into the viewfinder of the camera which in turn becomes a control room.