Artist and activist Jen White-Johnson plays Maestro on VR. Credit: TownFuturist Media.

This interview is the first in a series published by the BIMA Immersive Tech Council which aims to draw attention to the groundbreaking work happening in the area of art, technology, and innovation.

We have also published an article giving insight into how arts and culture are leading the way in digital innovation. This first interview delves into the pioneering work of Leonardo, a network of transdisciplinary scholars, artists, scientists, technologists and thinkers, and in particular their recent programme: the Criptech Metaverse Lab.

The lab was co-produced by Leonardo/ISAST and San Francisco-based cultural incubator Gray Area in 2023 to address accessibility challenges in virtual reality (VR), augmented reality (AR), and spatial audio by enabling disabled creators to actively shape the future of immersive technologies. This pioneering collaboration brought together ten disabled creatives—Panteha Abareshi, Indira Allegra, Nat Decker, Antoine Hunter, Melissa Malzkuhn, Maia Scott, Stephanie Sherriff, Andy Slater, Jennifer White-Johnson, and Iris Xie—as well as industry partners Meyer Sound, VIVE Arts, and VIVERSE, to experience immersive artworks and technologies, engage in critical discussions, and create new speculative artworks.

The following interview took place across several conversations in November 2023 with members of the Leonardo team: Vanessa Chang (VC), Director of Programmes, Leonardo; Lindsey D. Felt (LF) Disability and Access Lead, Leonardo; and Jennifer Justice (JJ) and Frank Mondelli (FM), disability usability researchers on the Criptech Metaverse Lab). Further bios for the interviewees are provided below. This interview was edited and condensed for length and clarity.

Recoding Criptech exhibition. Photography courtesy of Rich Lomibao.

Can you introduce Leonardo, its mission and work?

VC: Leonardo was founded in 1968 as a journal dedicated to advancing interdisciplinary art, science and technology. Over the past 60 years it’s grown into a transdisciplinary network and platform focused on convening, researching, collaborating and disseminating best practices in art, science and technology worldwide. We’re in a really complex moment and we think creative solutions are absolutely necessary. One of our major flagship programmes is the Criptech Incubator, which is our art, science and technology fellowship for disability innovation. I also oversee the artists commissions, artist residencies, and fellowships.

What was your journey into working with Leonardo and the Criptech Metaverse Lab?

VC: As I came out of grad school, I started doing more curatorial work in the art and technology scene in San Francisco. There was a lot of discourse around artistic innovation using technology, but there was a lack of critical thinking about who these technologies are for and how they use them. If you’re going to think about technology and embodiment, then you have to think about the role of disability: what you assume a body is, what a body can do when it engages with technology. I noticed a gap around the intersection of art, disability and technology. That informed our (Lindsey Felt and my) thinking around embedding access as we organised Recoding Criptech in 2020, a show about disability, innovation, and technology. There was a lot of practice-based work in the exhibition, and that framing stayed with us. So we took the idea for the Criptech Metaverse Lab to Leonardo and said: this is an important set of conceptual interests and commitments that resonates with what Leonardo is doing and its legacy.

LF: Vanessa and I met in grad school at Stanford. We were in parallel programmes and we had an immediate connection. Vanessa approached me about a curatorial fellowship in 2018 with the idea to explore the nexus of disability innovation in the Bay Area. My research focuses on histories of disability innovation—how disabled people have fundamentally shaped our communication practices and some of the key technologies that we use today. This is an area of personal interest to me as well, as a deaf person and bilateral cochlear implantee who uses many assistive technologies. So there was a natural alignment of interests. The curatorial fellowship culminated in the Recoding Criptech exhibition. We realised that a number of the disabled artists featured in the show didn’t have access to the resources and knowledge they desired to advance their technological skills in their art practices. So we felt this was a timely and urgent space for additional work, and that’s how the Leonardo CripTech Incubator and Criptech Metaverse Lab came about. One of the goals of the Criptech Incubator was to expand impact and build the pipeline for disability innovation, which is part of my role as Disability and Access Lead at Leonardo.

Artwork by Jennifer Justice in the Recoding Criptech Exhibition. Photography courtesy of Rich Lomibao.

JJ: I’m an artist. I’m legally blind, hard of hearing, and neuro-divergent. I don’t always lead with that, but it’s pertinent to what we’re talking about today. I went through the traditional art school programme. During this time I started thinking: who am I making art for? It became very important to me to make sure my community was represented, my friends – low vision friends, blind friends, Deaf and hard of hearing friends, friends with mobility impairments. I became interested in investigating the intersection between technology and art making, and how it creates or denies access for audiences. I was part of the Recoding Criptech exhibition. It was exciting for me to delve into the emerging technology of 3D printing. My day job is as an Access Technology Specialist with a college in Northern California. It’s a fertile space for me professionally as well as in my artistic practice.

Frank (Mondelli) and I were involved from the very beginning in the design of the lab and I recommended a number of fellow artists for the cohort. Access was always front and centre in terms of how we wanted to frame the lab. We wanted to make sure everyone was being heard. It was ambitious because that’s not normally how industry does things. We knew there would be frictions. But we wanted to make sure it was a valuable experience for everybody, in particular for the artists as a historically disenfranchised group of people. We wanted it to be valuable for them economically and creatively. That was very important to me personally.

FM: I’m an Assistant Professor of Japanese in the Department of Modern Languages, Literature and Cultures at the University of Delaware. At the time of the lab, I was just finishing off my PhD at Stanford and a postdoc fellowship at the University of California Davis. A colleague of mine recommended me to work on the Criptech Metaverse Lab as a researcher. I’m not a full time artist like Jennifer but in my final year at Stanford I did create a musical EP chronicling my own experience with disability, since I’m hearing impaired. In the research archive, I sometimes find it hard to find records of disabled people speaking about themselves in their own words, so I wanted to make something inspired by my research that also centred a disability perspective. For the Criptech Metaverse Lab, Jennifer and I helped to develop the project with Vanessa, Lindsey, Claudia Alick, and Niki Selken to figure out how it worked on the ground. Of course once things really got rolling our job was to primarily focus on the research and the online archive.

Artist Nat Decker wears an HTC VIVE XR Elite headset. Credit: TownFuturist Media.

Can you talk a bit about the methodology you used for the lab, and the term ‘criptech’? Where does that term come from? And could I also ask you to reflect on why you felt it was important to apply that methodology in this field of immersive technologies?

LF: ‘Criptech’ derives from the term ‘crip technoscience’ developed by two brilliant disability scholars Aimi Hamraie and Kelly Fritsch back in 2019. It highlights the way disabled people produce their own valuable knowledge through encounters with the world. It’s both a kind of politics and a political stance that unapologetically values disability identity. It references the way disabled people hack technology and remake systems around them. How we dismantle those systems so they can better navigate the world and make environments more usable. And it’s a practice that’s both highly personalised and communal that’s been documented for hundreds of years.

When we started developing the lab, we began with the premise: what would happen if you brought a group of disabled creatives into the room who have unique, lived knowledge of navigating different technologies in their lives? We were interested in seeing what new kinds of practices or experiences might emerge when disabled folk reflect in real-time how they are navigating through and around these systems. For example, what if you have a blind person in a virtual-reality experience that is primarily visual? How will they navigate that space? What kinds of questions will they ask?

VC: We felt we were in another hype cycle but also an accretion of open source interest in VR and wrangling over this term metaverse. It struck me as a fascinating moment of discursive, technological social push and pull that had a lot of potential but also dovetailed with the arts, innovation, and access work that we had already been talking about. There’s been access work in XR previously but not from this creative access angle. There needs to be space for fun and play and joy because there’s so much frustration. So how do we foster that space and make it into something generative?

There were moments of improvisations in direct response to fundamentally incarnated points of inaccessibility. So, to return to your question of why apply this methodology to immersive technology, it’s because it’s an emerging technology. It’s important to have these interventions now. But we also struggled because the technology does also exist now. That’s why we did a lot of speculative design work during the lab. What could the future look like? What could the experiences look like?

JJ: I know that immersive and online communities are very important to members of the disabled community. There’s a lot of untapped potential. I don’t think we’re there yet but it’s exciting. We’re in this early stage. When I went to college I started using computers but they weren’t accessible to me. Then Apple released their accessibility suite. It was revolutionary for me to suddenly be able to enter a space I couldn’t previously participate in. It changed my whole life. I depend on assistive technology every day now. I think there are a lot of people that are restricted in terms of getting out for whom these virtual environments can be really meaningful. Like a lifeline. We (the disabled community) have to be part of the whole lifecycle of creating the infrastructure and technologies that meet our goals. That’s what’s so important for me about this project.

We’ve been doing this work informally since we were kids. You start devising your own accommodations when you’re very young, it becomes second nature to problem solve. If there’s inaccess, and you have a healthy sense of self esteem, you just say, “Well, screw that, that’s not right. I’m going to just jump through that. I’m going to get closer to the painting anyway, or touch the sculpture, or make friends with the museum guard to learn more about the exhibition. So it’s subversion, just strategising or improvising. There are power dynamics that I think most people, able-bodied people, don’t even consider. The reality is everyone will be disabled at some point in their life. It’s a natural state of being. So acknowledging that disability is a part of our lifespan is a more compassionate way of looking at design.

Sound artist Andy Slater tries to navigate WebVR while Leonardo Director of Programs Vanessa Chang and VIVE Arts Head of Global Partnerships Leigh Tanner offer live description. Credit: TownFuturist Media.

Historically, how have disabled creatives informed the development of emerging technologies – either as part of the formal design process, or as Jennifer describes, in a more subversive way?

FM: Disabled people were involved in the invention of so many crucial technologies, for example the invention of the telephone. There’s a scholar, Mara Mills, who came up with the concept of “assisted pretext”. This is the idea that deaf people are involved at an early stage in the design of assistive technology but at the first chance it’s switched to something that’s not for disabled people but instead a much larger, more commercially viable format for better return on investment. Then the disabled people who were originally involved are locked out. It’s something that gets repeated throughout history. For example, many electronic firms were set up in post-war Japan building hearing aids or involved in assistive technologies. But those companies often don’t highlight that in their histories, and it’s hard to find information on those details without going straight to primary sources.

Why did you feel it was important to have had these roles (disability usability researchers) for the lab? What did it mean to you both (Jennifer and Frank) to accessibly research and capture the lab?

JJ: I’ve been part of many focus groups where I was brought in and just given a $50 voucher to get my opinion about technology that clearly wasn’t designed by or with disabled people. And that was an awkward position to be in because you don’t want to totally shut people down, but at the same time it’s an uneven balance of power. So I wanted to make sure my friends weren’t put into a situation like that. The team made sure that accessibility wasn’t just boilerplate, but made sure people felt comfortable and were in a democratic space.

FM: I remember one time I went with a friend of mine to a showcase of new assistive technology in Japan. We saw a Ferris-wheel like contraption. The idea was you could strap your wheelchair in and use it to go up a set of stairs. My friend in a wheelchair was like, I would never get in that deathtrap! I’ll never forget that. Some engineer saw a staircase and thought wheelchair users want to go up stairs, right? So we have to design something that lets them go up stairs. But that’s not what many wheelchair users want. They just want to get in the building. It’s not about the spectacle of access. It’s about the end result. So many would say just build a ramp, they work just fine.

It’s about trying to get engineers to consider just simple stuff like the social model of disability vs the medical model of disability. The medical model is the idea that disability is located only in the body as a purely medical condition, while the social model encourages us to see how states of disability are created through conditions exterior to the body. There are other models of disability, but the basic idea is that we can engage with disability through infrastructural, social, and other kinds of lenses. There’s more than one way to look at the world. There’s more than one way to think about access. So you need researchers in the room to observe and see what’s going on and then write about it in a productive way.

How did you start planning the lab? You were saying how play was an important aspect – was that present at the outset of the lab or did that emerge through development?

LF: Experimentation was always a key word for us. We wanted to create a play space but we weren’t sure to what extent the group would take that up. There were real moments of frustration in parallel with the moments of play too. It wasn’t rainbows all day.

One thing that was really important in the planning was that this took place in the pandemic. We’re working with a vulnerable community. So we were trying to think about a hybrid model. We were all remote. We were all reliant on virtual technologies. I think that’s why there was a resurgence in interest around VR because of what it could mean for all of us to be in a space together when we couldn’t be in person. And in some ways that did motivate this question of what would happen when you brought a creative angle to working with some of these existing technologies.

VC: There were a few tensions we were working through. As Lindsey mentioned, we were trying to draw a line between experiences of friction and generative experiences of play. The lab was planned by a community of disabled and non-disabled leadership. We were looking at whether it should be in person or virtual. What does it mean to gather? What does it mean to gather in the pandemic? How do we kind of create the conditions for collaboration when we also need to create conditions for rest and for people to be together?

There’s this notion of “crip time” [the concept that addresses the way that disabled people experience time differently and need flexibility]. So any time you introduce a group of people with various access needs into a space, the schedule doesn’t obey. So for example, one mode of reflection at the lab was “Rose Bud Thorn”, offered up by Niki Selken, the previous Education Director of Gray Area. It was a framing for the participants’ experience of the lab. What’s a thorn (something that is sticking)? What’s a rose (something that you enjoyed)? And the bud is a generative moment. So we had that up on the wall. But we had two blind participants for whom that was not immediately accessible so we put that into documents and read them back to them. It was an invitation that had to be mediated in a few different ways. And that takes time.

The researchers would digest that material as framing for the speculative design work. Jennifer led a 3D audio description workshop in collaboration with Maia Scott, a blind artist who works with labyrinths. Visual descriptions are usually for 2D images, like photographs. So how do you describe something in 3D as though you’re moving through space? There was also a speculative design workshop which Jennifer led with another researcher Laura Johanowitz to develop a set of prompts about where and when the participants wanted VR to be in different time frames. So for example, “It’s 15 years in the future and you wake up in the metaverse: what’s the thing that brings you the most joy?” It’s an invitation for a concrete lived experience.

Melissa Malzkuhn uses the pass-through feature on the VIVE headset to sign with her interpreter Santana Chavez. Credit: TownFuturist Media..

Can you talk about how you facilitated access for the participants and the process of making sure everyone’s access needs were met?

FM: Claudia (Alick) was the real expert on that kind of work – reaching out to everyone in advance to check their access needs. We (Jennifer and I) helped design the three days of the lab. We were also present as participants, but we had this extra job as researchers and we both kept notes, writing down things we were seeing and hearing. It was a matter of seeing things happening on the ground, and then relating that back to theoretical concepts in the documentation. We were cultivating an open space where people felt comfortable to speak their access needs out loud. We had a session before anything even started where we all introduced ourselves and just said, “We’re disabled researchers. We’re with you. This isn’t a sterile research environment. This is something we’re doing together. This is a new kind of research built from the ground up. We’re going to be productive with this.” And, you know, I think we fulfilled that promise.

Access is a process. It’s not going to be perfect. But it’s either doing something or not doing something. For me, it’s important to do our best but expect that there are going to be access failures. Sometimes I talk with other researchers or activists and there’s this idea that if we can’t get the captions exactly right, we can’t do the event. I understand where it comes from because you don’t want to be another person adding inaccess to the world. But there’s an important distinction I make: are there disabled people involved with some sort of substantial power in the operation, and are we building with as much access and goodwill as we can given the circumstances? So we just have to do our best, take feedback seriously, and always try to improve.

Can you summarise some of the key learnings and findings from the lab?

LF: There were several different misfits that were happening and we wanted to document what they were. “Misfit” is a term introduced by Rosemarie Garland Thomson, a disability studies scholar, to reflect the idea that environments are not designed for certain bodies, and as a result, there are access frictions that create inaccessibility or even trauma, pain, or harm. Some of the outcomes that we documented were around fundamental hardware design misfits. We also wanted to draw a distinction with the software design misfits too, at the level of code or how the platform was designed. Another misfit we noticed were the user interaction frictions and also cultural relevance frictions, the latter of which identified moments when the participants didn’t see themselves culturally represented in the experiences. For example, Deaf folks who wanted to sign in VR, or when our Black participants could only select a white avatar. One of the moments that most deeply struck me while observing one of the VR experiences—the VR headset couldn’t register that a participant was seated and not a standing body. What appeared on the screen was a squashed avatar, so a real misrepresentation of that body in space. In some ways, the hardware misfits became the most prominent simply because they inhibited some users from even turning the headset on. For our recommendations, there was some discussion we had with Frank and Jennifer about how to approach this given the sheer magnitude of the issues that need to be addressed, but we wanted to be strategic and name the ones that were very evident and would have high impact.

Artist Qianqian Ye and facilitator Laura Cechanowicz Ye’s AR work, Kai Hai. Credit: TownFuturist Media.

What are your reflections on the lab now?

LF: It was an amazing experience for all the creatives to come together and see and hear about each others’ practices. The sense of community was so powerful, especially in that time of the pandemic. That’s one of the most positive outcomes from the lab: the opportunity for disabled creatives to be in shared space with each other and come up with new ideas. But it was only at the end of the lab we started getting into the speculative design work. We needed to give folks time to wrap their heads around it all.

JJ: At this point VR is fairly new in terms of a commercial audience. But the design has come from video games. Point-and-shoot games are highly visual experiences. Well, why is that? That style of game is what people are most familiar with. At some point during the lab I thought, why do we even need goggles? Are they essential? For example, one of the blind participants couldn’t even get past the tutorial on one of the games. So she started doing these full body motions to break out of the experience and to play and experiment with the bounds of the world. It was so great. Disabled artists are used to that experience where we encounter a technology that doesn’t work for us, so being able to harness creativity out of that was really exciting.

VC: There were two things that could have shored up the experience and got us more firmly to the creative space. One is more time. We could have spent three days just on spatial audio, and three days just on VR. But there’s also the baked inaccessibility in some of the tools that meant that couldn’t happen. Some of the blind participants were not even able to turn on the headset. So there’s a fundamental barrier that prevented them from even starting the experience. How do you remove or mitigate those access barriers to get to the creative space? What is a meaningful way of bridging technological and platform inaccess? I think with some of the tools it ended up having to be speculative because the engagement was not available.

How does this project connect with some of the other R&D work that Leonardo is undertaking?

VC: We have different models – some for emerging creatives, some for more established artists. The Creative Impact Labs are an international initiative to teach a cohort of local creatives how to use a particular suite of tools which they use to develop an artwork. Most recently, the Creative Impact Lab was in Amman, Jordan led by the artist Jessica Jabr who did workshops around AR, basic AI, and 3D printing tools for around twenty young Jordanian adults. The long term goal is to support community exchange, workforce development, and creative enterprise work. So that’s one model of R&D. Leonardo-ASU Imagination Fellowship – a virtual, global programme where fellows develop experimental media projects that address climate, democracy, social structures, and interspecies relations. We’re very interested in sustaining meaningful change.

What is your advice to commercial companies who want to embed greater inclusivity and access? What do you think needs to change in order for there to be more equity and representation in the design of immersive/metaverse experiences and tools?

LF: Be open to collaborating with organisations that are already doing this work and have established trust with disabled and marginalised communities. Doing it within the walls of a company alone can be tricky, and it’s how you alienate communities. So those partnerships are very powerful. We should include disability representation at every single level, from the ground up and the top down. You need access knowledge built in from the beginning of the creative process. This is a task for everyone. It shouldn’t just fall to the disabled community.

JJ: Pay attention to what we recorded and made tangible through the archive. Employ disabled engineers and designers. Make sure that disabled people hold leadership roles in designing creative tools and involved throughout the entire R&D lifecycle. Fully integrate them, not in just a tokenistic way. Having disabled engineers and artists hired by companies is really important. Black disabled creatives. Native American disabled creatives. What are the different perspectives that are missing? Who’s not at the table? I wanted to add that our CripTech Metaverse team (all of whom are accomplished professionals in their fields) had design fixes for many of the access problems we encountered with the hardware. We were quite confident that our input could add value to the products’ usability.

VC: Our work is about reorienting the relationship between disabled people and technology as one that isn’t curative or rehabilitative. There’s this long history of innovation and expertise because disabled folk have had to forge access where there wasn’t any. Our main recommendation is to build disabled folks into every aspect of the process. That will lead to better technologies, better products, better artworks.

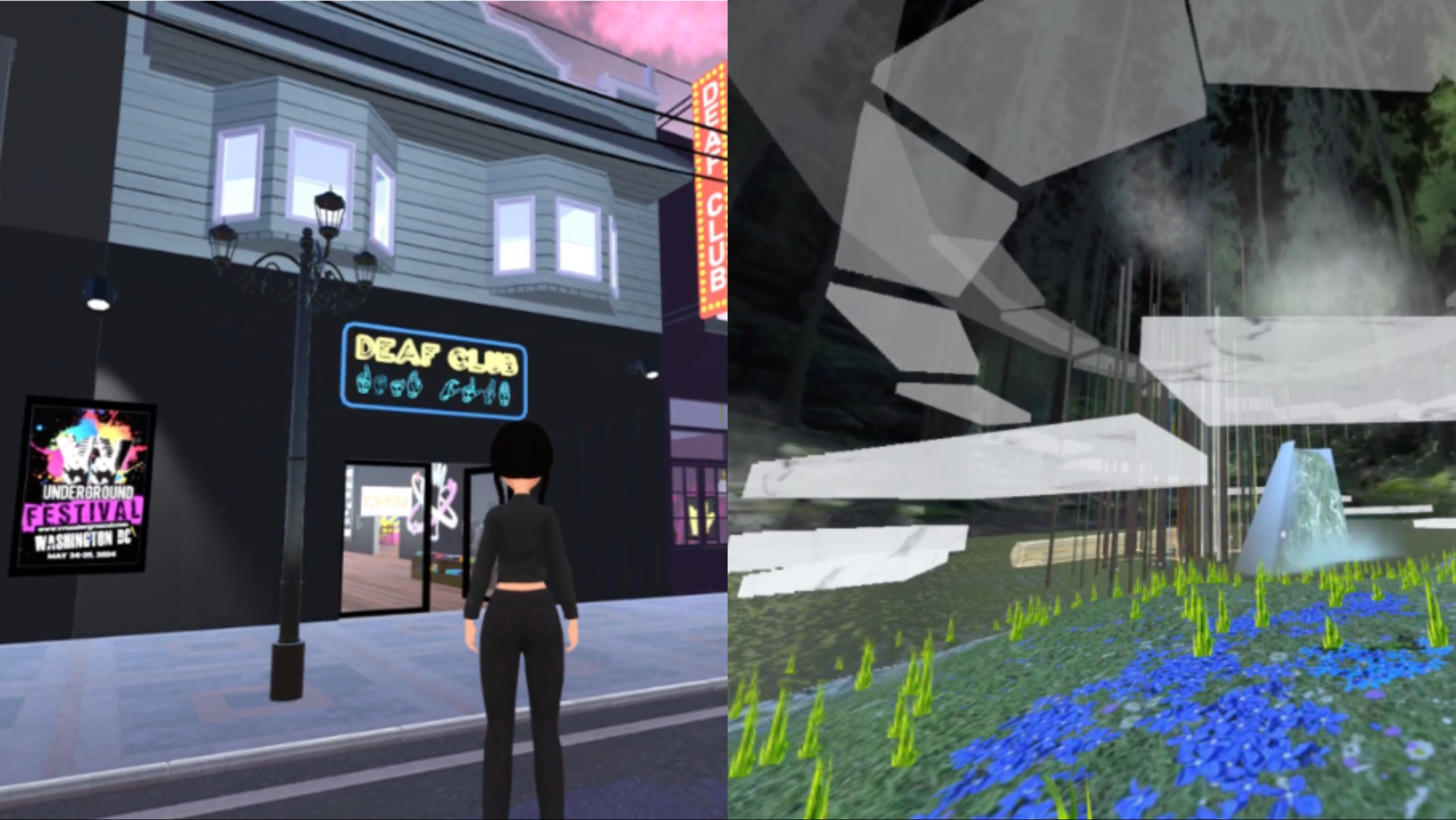

VR still, The Deaf Club, Melissa Malzkuhn, 2023, courtesy of artist. \\ VR still, TEXERE: A Tapestry is a Forest, Indira Allegra, 2023, courtesy of artist.

—

Criptech Metaverse Lab Commissions

The 2023 Gray Area Festival: Plural Prototypes featured the world premiere of three new artistic prototypes by artists Melissa Malzkuhn, Indira Allegra and Nat Decker, selected from the CripTech Metaverse Lab. Their speculative VR artworks delve into the realm of accessibility in the metaverse, adding depth to our perception and experience of these emerging realities.

Two of the works were developed on HTC’s VIVERSE in collaboration with VIVE Arts. Malzkuhn’s project reimagines the concept of the Deaf club, a vital part of Deaf communities globally, within the digital realm of the metaverse. A living weaving that sings, Allegra’s TEXERE: A Tapestry is a Forest is an immersive platform for collective grief and memorialization. Decker’s TOUCH, produced in collaboration with virtual art space New Art City, is an interactive poem exploring narratives of the boundaries of physical intimacy and infraction from the perspective of a queer disabled person. More information about the artworks can be found on the Criptech Metaverse Lab archive.

Further info:

Contributor Bios:

As a curator, writer and educator, Vanessa Chang builds communities and conversations about art, technology and human bodies. She is Director of Programs at Leonardo/ISAST. She holds a Ph.D. in Modern Thought and Literature from Stanford University. Curatorial projects include Experiments in Art, Access & Technology (E.A.A.T.) at Beall Center for Art and Technology, Recoding CripTech at SOMArts Cultural Center, Intersections at the Leonardo Convening at Fort Mason Center for the Arts. She has appeared on NPR’s On the Media and State of the Art, and her curatorial work has been profiled in such venues as Art in America and KQED Arts. Her writing has been published in Wired, Slate, Noema, Los Angeles Review of Books and the Journal of Visual Culture, among other venues.

A scholar, writer, and educator, Lindsey D. Felt curates and builds frameworks for access/accessibility across digital, arts and educational platforms.She is the Disability, Access, and Impact Lead at Leonardo/ISAST, where she helps direct the Leonardo CripTech Incubator. She is also a lecturer at Stanford University in the Program in Writing and Rhetoric, where she teaches courses on disability, technology, and accessible arts curation. She holds a Ph.D. in English from Stanford University. Her research and writing has been published in Catalyst: Feminism, Theory, Technoscience, Ground Works, After Universal Design: The Disability Design Revolution, among other venues. She co-curated Experiments in Art, Access & Technology (E.A.A.T) currently up at Beall Center for Art + Technology, UC Irvine and Recoding CripTech during a 2019-2020 curatorial residency at SOMArts Cultural Center in San Francisco. Her curatorial work has been profiled in Art in America, KQED Arts, SFMOMA’s Raw Material podcast, the Disability Visibility Project, and others.

Jennifer Justice is an artist and writer living in Mendocino County. Her recent writing appears in Curating Access: Disability Art Activism and Creative Accommodation (Routledge) and a forthcoming issue of Leonardo Journal. She creates speculative sculptural environments that invite performative multi-sensory encounters with handmade and digitally-crafted artefacts, and her work has appeared widely in exhibitions in the US and Australia. She works as an educator and access technologist in higher education and previously worked in the Rehabilitation Engineering Lab at Smith-Kettlewell Eye Research Institute on a crowd-sourced audio description app. Her research focuses on the influence of disabled artists and communities in shaping emerging technologies.

Frank Mondelli is Assistant Professor of Japanese Studies in the Department of Languages, Literatures and Cultures at the University of Delaware. His research and teaching interests focus on the material and cultural history of technology, media, and disability in modern Japan, including the history and politics of assistive technologies, videogames, and traditional craftwork. His current book manuscript explores the historical intersection of D/deafness, music, and technological and media spectacle in 20th century and contemporary Japan. His academic research is deeply influenced by his work in disability and Deaf rights advocacy in both the United States and Japan.