This article is a expansion of a talk I gave at the Digital Transformation conference here in London in 2019.

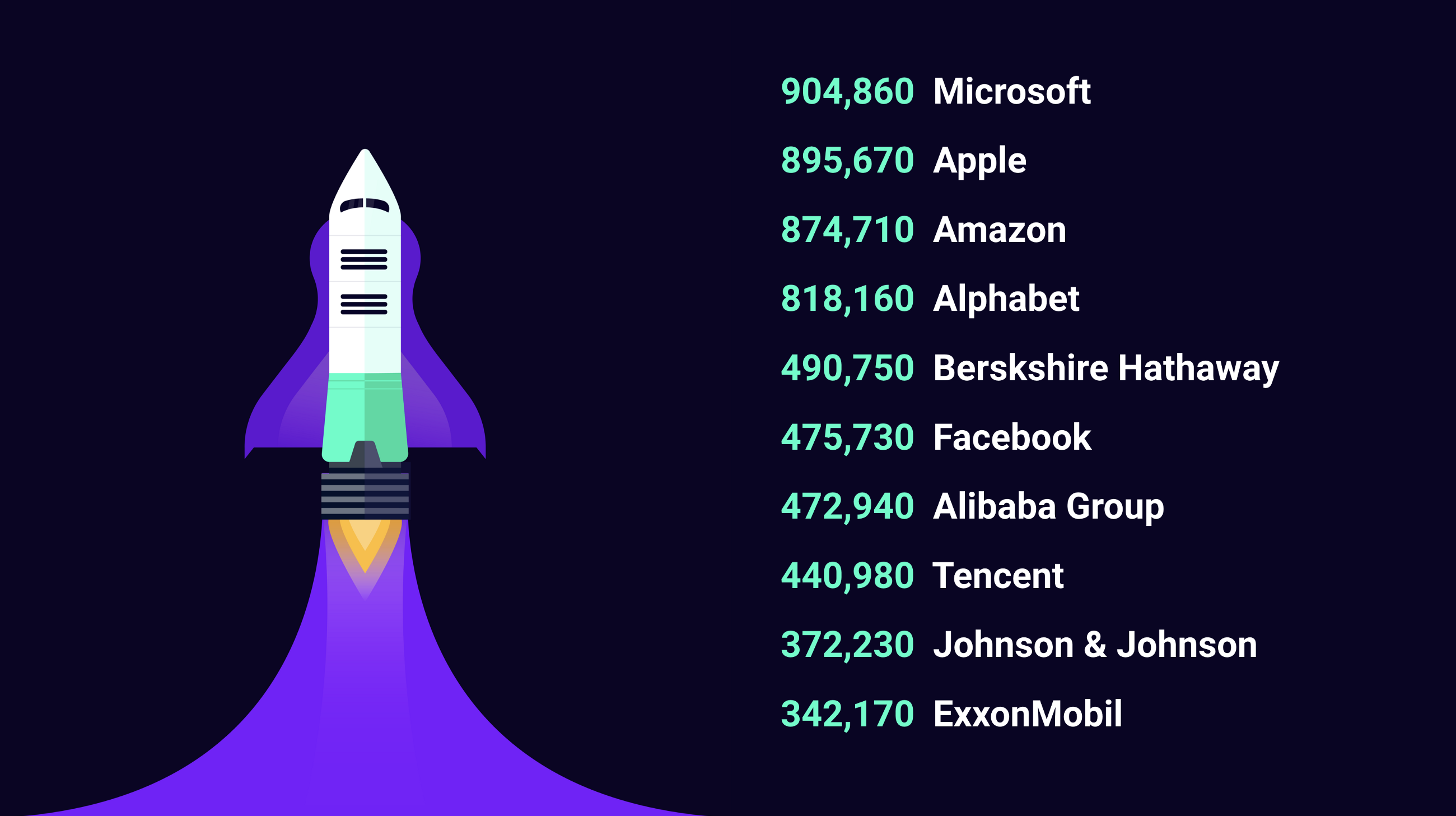

In 2015, 3 of the top 10 most valuable companies in the world were tech companies.

In 2017 this number grew to 5 out of 10.

Now in 2019 it’s 7 out of 10.

This is a trend that will be continuing, and it’s likely we’ll see a full 10 out of 10 by 2022.

When I talk about a ‘tech’ company in this article, I’m referring to one that scales to its audience primarily through software. Sometimes these tech companies also create hardware to enable this.

For any non-tech business in the top 100 most valuable, this must be a terrifying realisation.

To keep ahead, organisations must begin to think, innovate and work as effectively as the growing tech companies.

So, this article is an exploration of some stories and ideas on what these ‘tech’ companies do differently from ‘non-tech’ companies.

We all think we know the story of Netflix vs Blockbuster.

One of the greatest shifts in media consumption of our time. It seems obvious in retrospect why Netflix now sits at #52 most valuable company in the world. Blockbuster is now relegated to ‘failure to innovate’ blog posts (somewhat like this one).

But, if we travel back to 2013, things weren’t quite as black and white.

Some interesting facts on the Blockbuster/Netflix story that are often overlooked:

The CEO of Netflix offered to sell the company to Blockbuster for just $50m back in 2008.

Blockbuster was first to market with online video rental, beating Netflix to the post by quite a few months, with a large, existing customer base.

There was less than a years gap between Netflix and Blockbuster launching online video streaming services.

So, Blockbuster played many of the same moves Netflix did, often within a similar timeframe, and sometimes first to market. This isn’t often the story people remember.

It becomes even more uncertain when we look at the stock price of Netflix at the point that Blockbuster eventually filed for bankruptcy. Netflix was trading substantially lower than at it’s peak just a year before. Confidence in it’s ability to grow into the behemoth we see now was limited. The believers were media and technology sceptics, forward thinking investors and early adopters.

You could argue that the later rise in Netflix’s stock price during Blockbusters death was due to Blockbuster leaving the market rather than people’s confidence that they were poised to grow a strong foothold.

There’s a great quote from a former Blockbuster exec in Variety magazine from 2013 that really underpins this sentiment:

Management and vision are two separate things. We had the option to buy Netflix for $50m and didn’t do it. They were losing money.

Given what we’ve just learned about the state of Netflix and Blockbuster above, it’s not clear that Netflix would find a rapidly growing audience. This helps us understand the dilemma this particular exec was facing.

Why would this exec switch his time away from a large, multi-billion P&L? Netflix was a small, loss making market that required a huge continued investment. It had little validation of a growing customer base. Not to mention, the complexity of negotiating the deals needed to provide this type of service from the content producers side.

Blockbuster’s employees even lobbied against their own company for creating competing products (streaming, online rental etc). So, blockbuster responded by fighting to keep their employees in work, while still investing in new markets.

Blockbuster and it’s execs during 2008 to 2013 were mostly concerned with Walmart stealing customers from their existing physical rental business. They were less concerned with this small, loss making ‘niche’ product called Netflix.

It wasn’t obvious Netflix would prevail, even as Blockbuster died.

So, Blockbuster did a lot right. They fought hard to keep their employees in work and defend their incumbency. They innovated, and brought new products to market. Sometimes they did it first, but they still died.

And this is the key:

Management can do everything right, and still lose.

This is what Clayton Christensen describes as the innovators dilemma. It’s a key challenge for all organisations, tech or not, to understand how to break this.

Whatever size of company you are, there’s a small, niche, possibly loss making company that’s gunning to find incremental value in your market and outlast you.

Management and vision are two separate things.

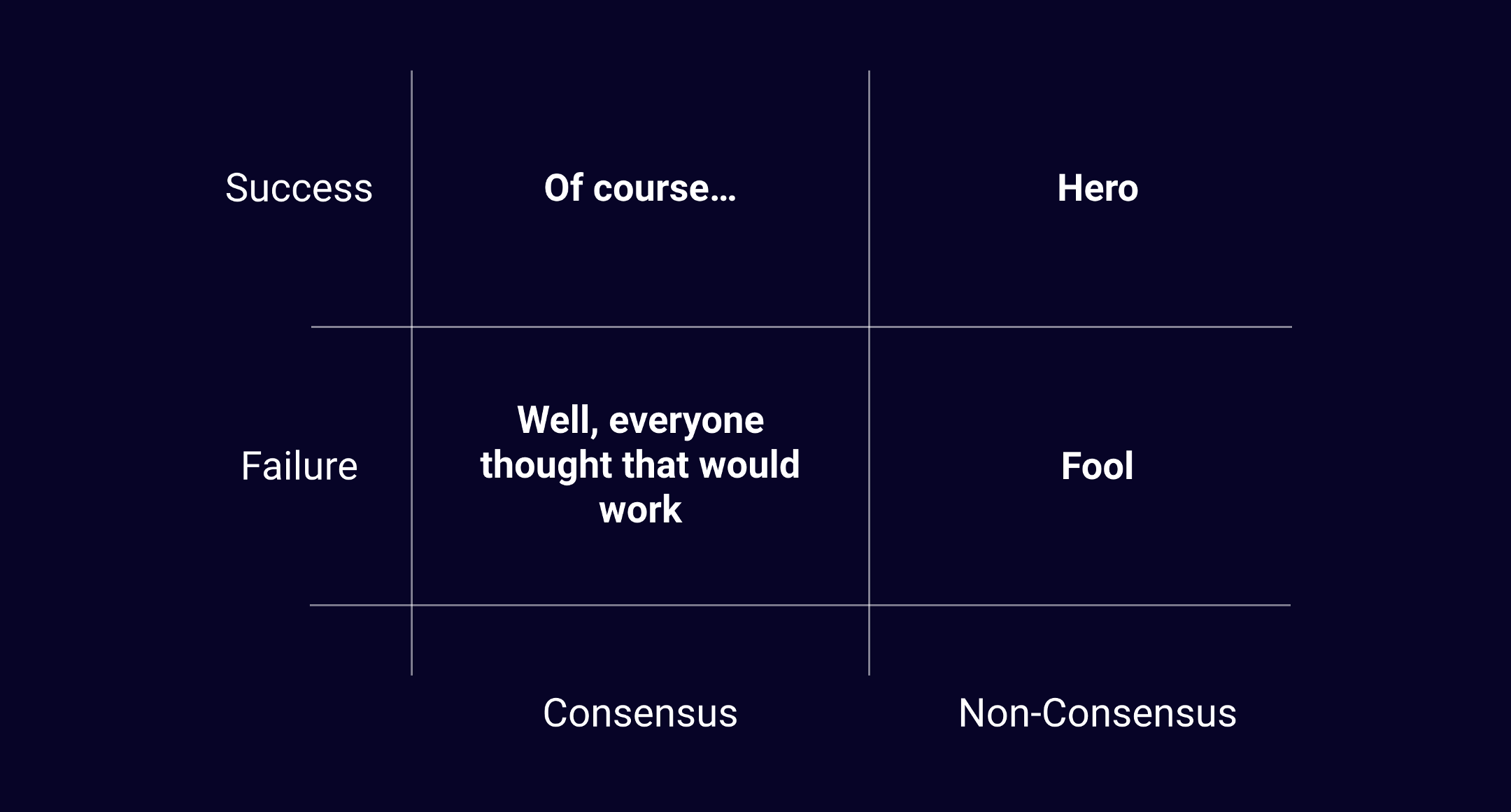

The consensus paradox is a good way to think about the challenge faced by the execs within Blockbuster at the time, and is explained by this question:

Would you rather succeed with an idea that no-one believed in, or one that everyone thought would work?

We’ve just learned how Netflix and Blockbuster’s battle wasn’t clear at the time. We post-rationalise these battles to make them seem more obvious than they were. Netflix was at the time a non-consensus idea.

When Apple created the iPhone, consensus amongst the tech pundits and Apple’s competition was that a physical keyboard was substantially better. This was a non-consensus idea, but a glance at our smartphones today tells a different story.

Currently, everyone believes that self-driving cars will become a key piece of our lives over the next 10 years or so. This is a consensus idea amongst the tech crowd today.

These non-consensus ideas often end up being financially, and personally more rewarding. Succeed in non-consensus and you’re labelled a Steve Jobs, a Jeff Bezos. So, given the chance, most people would prefer to succeed with a non-consensus idea.

But, when we try to look forward to what will happen, these non-consensus ideas are much, much harder to make a bet on.

Ask yourself, today, would you put your money and reputation on augmented reality smart glasses replacing our smartphones in the next 10 years?

Would you invest in the idea that money will be transferred primarily through messenger apps as easily as we send each other text messages?

These ideas, while realistic, are much harder to invest our full belief into until they’ve happened.

This consensus paradox creates interesting dynamics inside a company. If you pursue and succeed with a consensus idea, people applaud the success, they’re happy it worked… but they already knew it would. If you fail with a consensus idea, you’re consoled by your colleagues, they too believed it would work. “Don’t worry, we all believed it would work out”.

If you drive a non-consensus idea, and you get it wrong, it’s easy for people to believe that you wasted your time and effort on a concept that was ‘never going to work’. But, If you succeed with a non-consensus idea, you’re branded a hero. You’re a Steve Jobs or a Jeff Bezos, because you found value and changed peoples expectation.

It’s quite easy to pursue a non-consensus idea as a startup, you spend someone else’s money (VC), and if your idea fails, you wash your hands, and go try another idea.

Inside a larger company this can be much harder. You’ve built a name for yourself, and risen up the ranks over the course of many years. The risk of failure and reputation damage that a failed non-consensus idea can have is a much more bitter pill to swallow.

This is one of the key reasons organisational ecosystems focus on the consensus. They resist, then eventually follow those agents of change once consensus is found.

Its easy to pursue an idea that everyone believes will work, but the non-consensus can sometimes lead to greater reward, or entirely new forms of business. Working out how to go after both is a critical part of building a resilient business.

Management and Vision are two separate things.

Challenging management vs vision — why tech companies win

So how can we begin to challenge management vs vision? A key foundation of software is that a designer or developer can make a change to a piece of software, and that change can be instantly used by hundreds of thousands of users around the world.

Equally as importantly, we receive feedback on its effect instantly. Any failure can quickly be rolled back, help develop a new vision, while success can be rolled out to every user immediately.

This is the fundamental shift that technology has enabled in businesses.

A line of code can change a product instantly, and we can get feedback on its effect instantly.

This change has moved our teams closer to the customer than they’ve ever been before. Its enabled product to be developed at the speed of thought. This has enabled us to shift a good amount of that vision away from management, and into the hands of the people who work directly with customers every day.

This change has moved our teams closer to the customer than they’ve ever been before

This rapid pace of creating something, and understanding it’s effect at speed enables us to challenge both consensus and non-consensus ideas extremely quickly, and by those people who are closest to the customers or space.

It’s extremely important that we understand that our businesses, our tech platforms, our team structures and our processes for innovation have to leverage this key strength at its core.

Let’s look at an example of the difference this can make from one of our advisors, Bill Scott, ex VP Engineering and PayPal and Venmo, and who was an early team member at Netflix.

Technology and teams enabling vision

This is a story Bill told me about his work at Netflix, and his subsequent transition to Paypal.

During his time at Netflix, one of the things he worked on was the launch of the PS3 version of the Netflix product. There were many competing ideas in his team on how to drive value for the users, many different approaches to laying out the content, navigating, and discovering shows you may want to save for later.

Instead of simply building what they thought would work, they set about creating multiple versions of the same product, with different experiences, and they measured which created the most engagement with content from users. This helped them select the right path, and this winning version was further explored, experimented with and expanded.

Netflix really understood how to use technology to empower teams to be as close to the customer as possible, and they were relentless in experimenting with ways to find more and more value for their users. They structured their work around the principle of getting the team as close to the users as possible.

One of my favourite examples of Netflix’s dedication to customer value is their approach to displaying thumbnails of each piece of content. Each thumbnail you see is generated specifically for you, based on what Netflix thinks you like. For example, if I’m into romantic comedies, it would see a suitable scene in the content that represented a romantic comedy relationship, and they would overlay the shows graphics to generate a thumbnail. This helps me as a user understand the elements of the content that I would enjoy most, and it’s relevancy to me. A great outcome of having deep technology teams as close to the user as possible.

Now, when Bill moved from Netflix to Paypal, things were very different.

At the time, Paypal was struggling. They’d recently been acquired by eBay, and competitors were gaining traction in their market rapidly.

At the time, Paypal was struggling. They’d recently been acquired by eBay, and competitors were gaining traction in their market rapidly.

The consensus in eBay at the time was that large skill focused teams of vast headcount represented an efficient process (velocity!). Tonnes of engineers in one team, tonnes of designers in another team, and vision and success dictated by higher level managers and meetings.

This ‘efficient’ process meant it took almost 2 months to simply change the colour of a button on the checkout page.

This ‘efficient’ process meant that it took almost 2 months to simply change the colour of a button on the checkout page.

So, this process was actively working against the benefit that technology gives us to drive innovation with customers. There was no immediacy to this process, and no chance for experimentation. Teams were simply delivering what management thought would work, not working with the customers to discover value and prove it.

Bill deeply understood why this was a problem.

To show there was a different way, Bill took a hand-picked small team and built a war room. They discarded the “well-engineered” platform and the lengthy process, and picked up a set of open-source tools that let them move fast and deploy to users extremely quickly, as soon as an idea was formed.

Their first focus would be the most valuable part of the PayPal ecosystem, the checkout flow.

Over the next few weeks, they rapidly worked with the customer to create a vastly simpler, vastly better experience by experimenting, deploying and validating their ideas weekly. They measured success through abandonment rates, successful checkouts and other customer experience metrics.

This vision for change was coming from Bill’s team, not just from managers, and they could move extremely quickly to incrementally drive a far better experience.

They leveraged the ability of technology to put the team as close to the customer as they possibly could, and let them drive value.

So what happened to Paypal?

Well as we know, since this, they have rocketed into the Fortune 500, and are continuing to rise.